1. Why does pregnancy aggravate the symptoms of mitral stenosis?

Women with severe mitral stenosis often do not tolerate the cardiovascular demands of pregnancy because

1. Increase in blood volume by 30–50% starting at end of 1st trimester to peak at 20–24 weeks. This increases pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure thereby increasing risk of pulmonary edema.

2. Decrease in systemic vascular resistance. (In MS, SVR should be maintained)

3. Increase in heart rate by 10–20 beats/min—reduces diastolic filling time of LV.

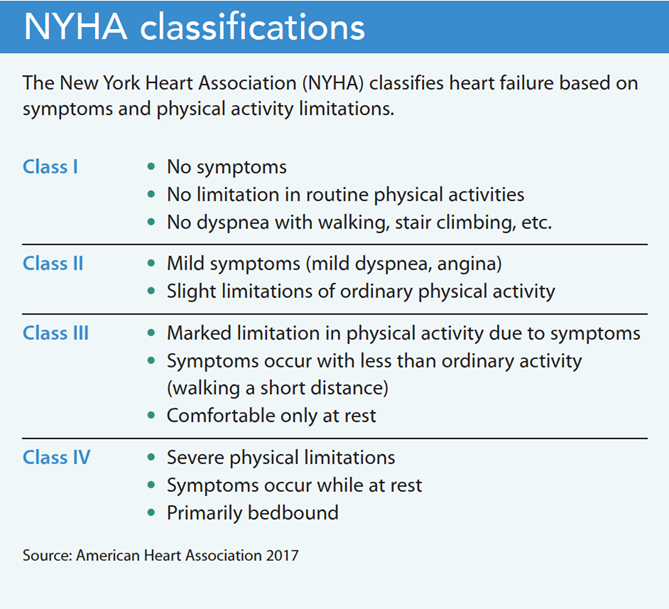

4. Cardiac output increases by 30–50% after the fifth month. CO returns to normal within 3 days of delivery. Because transvalvular gradient increases by the square of cardiac output, the transvalvular gradient increases significantly. This also raises LA pressure substantially to give rise to symptoms. During pregnancy, the patient’s symptomatic status will generally increase by 1 New York Heart Association class.

5. During labor and delivery, there is sympathetic stimulation causing tachycardia and further increase in cardiac output.

Also there is sudden rise in venous return to the heart due to auto-transfusion and IVC decompression. This may lead to decompensation.

6. Atrial fibrillation is associated with a higher risk of maternal morbidity in women with mitral stenosis. Both the loss of atrial systole and the higher ventricular rate result in diminished cardiac output and an increased risk of pulmonary edema.

7. Pregnancy also induces changes in haemostasis which contribute to increased coagulability and thromboembolic risk.

2. How will you diagnosis MS in pregnancy?

During pregnancy, the patient’s symptomatic status will generally increase by 1 New York Heart Association class due to tachycardia and increased blood volume.

Symptoms and signs associated with mitral stenosis include:

✓ Dyspnea,

✓ Hemoptysis,

✓ Chest pain,

✓ Right heart failure, and

✓ Thromboembolism.

Auscultation may reveal a

✓ Diastolic murmur,

✓ Accentuated first heart sound,

✓ Audible fourth heart sound, and

✓ opening snap.

The ECG may show

✓ Left atrial enlargement,

✓ Atrial fibrillation, and

✓ Right ventricular hypertrophy.

Echocardiography helps confirm the diagnosis, although careful measurements are critical because mitral valve area calculation based on Doppler ultrasonography may be inaccurate during pregnancy.

Diagnostic cardiac catheterization is necessary only when echocardiography is non-diagnostic or results are discordant with clinical findings.

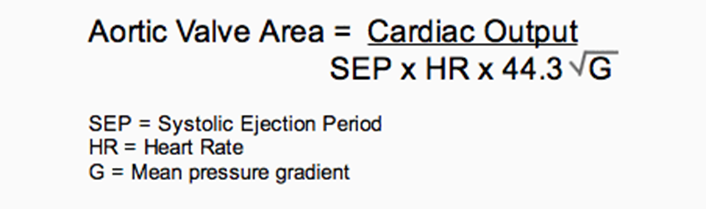

3. How will you calculate valve area?

The transvalvular gradient and transvalvular flow must be quantified to assess the severity of stenotic lesions. Hydraulic principles state that as valvular stenosis worsens, the valve orifice produces progressively greater resistance to flow, resulting in a pressure drop (pressure gradient) across the valve.

Gorlin and Gorlin derived a formula from fluid physics to relate valve area to blood flow and blood velocity:

Valve area α Blood flow ÷ Blood velocity.

The final Gorlin formula then becomes

Valve area = CO÷[(DFP or SEP)(HR)]× 44.3×C×(P1 − P2)1/2

where CO is cardiac output (mL/min), DFP or SEP is diastolic filling period or systolic ejection period in seconds per beat, HR is heart rate in beats per minute, C is the orifice constant (aortic, 1.0; mitral, 0.85; tricuspid, 0.7), and P1 − P2 is the mean pressure difference across the orifice as determined by computer-assisted analysis or area blanketing. The 44.3 coefficient is derived from the energy calculation. √G = square root of mean pressure gradient.

4. What is Ortner’s syndrome and Lutembacher’s syndrome?

Ortner’s syndrome:

When patient develops hoarseness of voice from compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve from an enlarged left atrium, it is called Ortner’s syndrome.

Lutembacher’s syndrome:

Combination of presence of MS with atrial septal defect (of the ostium secundum type) with a left to right shunt – Lutembacher’s syndrome.

5. What are the signs and symptoms of MS?

History:

Four cardinal symptoms of CVS namely dyspnea, palpitation, chest pain, syncope should be made after patient own complaints. Feature of failure symptoms- decreased urine output, right hypochondrial pain, swelling of legs. History of fever for infective endocarditis. History of dyshagia and hoarseness of voice to rule out complications of MS.

Signs and symptoms of MS:

I. Due to decreased CO:

a. Low effort tolerance

b. Typical “mitral” facies—mild cyanosis of lips and cheek and malar prominence.

c. Easy fatiguebility

d. Syncope

II Due to increased LAP:

a. Pulmonary congestion giving rise to dyspnea, orthopnea

b. Hemoptysis as pulmonary venous hypertension results in rupture of

anastomoses between bronchial veins

c. Pulmonary edema

III. Due to LA enlargement:

a. Ortner’s syndrome (hoarseness due compression of left recurrent laryngeal nerve by left atrium)

b. Atrial fibrillation and thromboembolism

IV. Due to pulmonary hypertension, RV hypertrophy, and RV failure

a. Chest pain due to RV ischemia in severe pulmonary hypertension

b. Raised JVP

c. Right parasternal heave

d. Tricuspid murmur

e. Hepatomegaly

f. Ascites and edema.

V. Hemoptysis in MS causes:

- pulmonary apoplexy,

- winter bronchitis

- pulmonary hemosiderosis

- pulmnary infarction

- bronchopneumonia

- anticoagulants usage

MITRAL FACIES:

The presence of mitral facies (pinkish-purple patches on the cheeks) indicate chronic severe mitral stenosis leading to reduced cardiac output and vasoconstriction. The pinkish patch is due to vasodilation of cutaneous vessels cause of low cardiac output.

Malar flush:

It is a plum-red discolouration of the high cheeks classically associated with mitral stenosis due to the resulting CO2 retention and its vasodilatory effects. Someone with mitral stenosis may present with rosy cheeks, whilst the rest of the face has a bluish tinge due to cyanosis.

6. How will you assess the severity of MS?

Pressure Half-Time Method of calculating Mitral valve severity:

Pressure half time (PHT, T1/2) is defined as the time needed for the peak transvalvular pressure gradient to fall to its half value, in milliseconds (ms). The faster the gradient falls, the easier the passage of blood through a valve, and vice versa.

Thus, high diastolic transmitral PHT indicates a narrowed valve area. PHT is always proportionally related to deceleration time (DT): . The decline of the velocity of diastolic transmitral blood flow is inversely proportional to mitral valve area (MVA), and MVA is derived using the empirical formula MVA (cm²) = 220 / PHT.

Grading the severity of mitral stenosis:

| Mitral stenosis | MEAN PRESSURE DECREASE | PRESSURE HALF TIME | VALVE AREA |

| MILD | < 5 mmHg | <139 ms | 1.6-2.0 cm2 |

| MODERATE | 6-10 mm Hg | 140-219 ms | 1.5-1.0 cm2 |

| SEVERE | >10 mm Hg | >220 ms | <1.0 cm2 |

7. What is the differential diagnosis for a mid-diastolic murmur?

Differential diagnosis for a mid-diastolic murmur:

- Cor Triatriatum

- Left atrial myxoma

- Ball valve thrombus

- Endocarditis

- Massive mitral annular calcification

8. What is the diagnostic criteria for Rheumatic fever?

Diagnosis of Rheumatic fever:

In rheumatic Heart disease, mitral valve alone is affected in about 50 percent of individuals.

Duckett-Jones criteria:

For diagnosis of rheumatic fever there should be either 2 major or 1 major + 2 minor criteria present.

Major

- Carditis

- Sydenham’s chorea

- subcutaneous nodules

- erythema marginatum

- arthritis

Minor

- Past history of RHD

- Fever

- Arthralgia

- prolonged PR on ECG

- increased ESR or CRP

- leukocytosis.

Infective endocarditis in MS – it is less common in isolated lesion than in patient with MS and MR.

9. What are the preoperative investigations you will do to assess MS?

Exercise tolerance testing: This provides an objective measure that may unmask poor functional ability in patients who have decreased their activity with the onset of symptoms.

Echocardiography: In addition to providing information on the severity of the lesion, echo may give information on any developing pulmonary hypertension and right heart dysfunction. In general, the LV continues to function well. In asymptomatic patients, where the systolic PA pressure is <50 mm Hg, non-cardiac surgery is considered safe.

ECG: AF is common, although p-mitrale may be noted if still in sinus rhythm. In ECG feature of RVH may be evident as right axis deviation, R wave in V1 more than 5 mm. Dominant R wave in right leads , R/S ratio more than 1 . dominant S in precordial leads. Sum of R wave in V 1 and S wave in V6 more than 10.

CXR – splayed carina , shadow within shadow due to left atrial enlargement , straightening of left heart border { normally the pulmonary bay is concave, it becomes convex in mitral stenosis, hence left heart border becomes straightened.} kerley b and a lines.

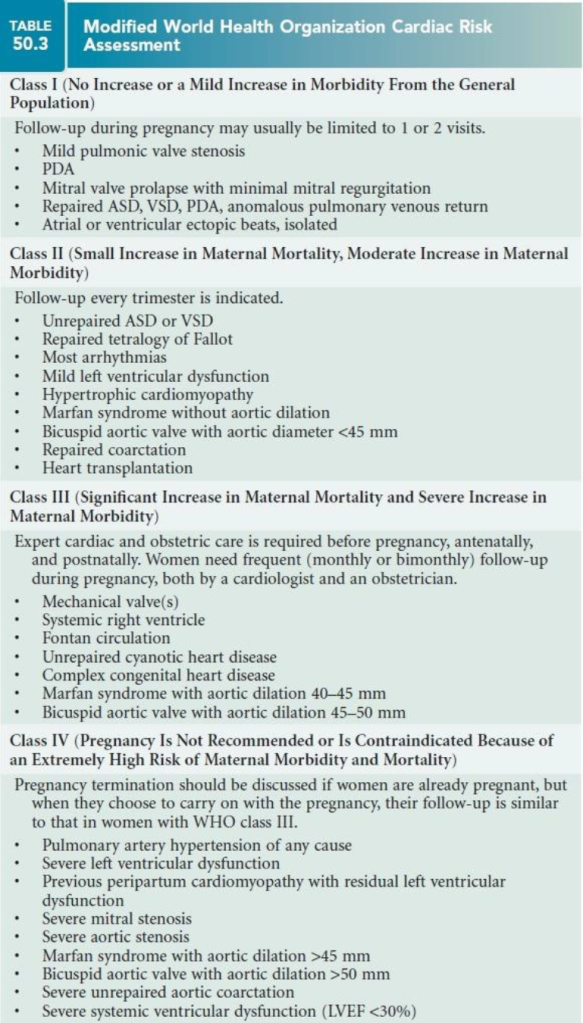

10. How will you do Cardiac Risk Stratification During Pregnancy?

➢ Several risk assessment tools have been proposed to stratify cardiac risk during pregnancy. By using these risk scores it may be possible to predict whether the woman will tolerate the pregnancy.

➢ Three risk assessment tools commonly used to predict maternal CV events during pregnancy are the

✓ CARPREG (Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy),

✓ the ZAHARA (Zwangerschap bij Vrouwen met een Aangeboren Hartafwijking-II, translated as Pregnancy in Women With CHD II), and

✓ one developed by the World Health Organization (WHO).

11. Explain the Obstetric management in MS:

The following guidelines discussing mode of delivery in women with mitral stenosis, including severe mitral stenosis, were identified:

RCOG Study Group on heart disease and pregnancy. (Steer)

• “Vaginal delivery, with epidural analgesia, is preferred for the majority of women. Invasive monitoring should be used in symptomatic women and those with severe MS. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be used.”

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy.

• “Vaginal delivery should be considered in patients with mild MS, and in patients with moderate or severe MS in NYHA [New York Heart Association] class I/II without pulmonary hypertension.

• Caesarean section is considered in patients with moderate or severe MS who are in NYHA class III/ IV or have pulmonary hypertension despite medical therapy, in whom percutaneous mitral commissurotomy cannot be performed or has failed.”

The Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (2nd edition) (RHDAustralia)

• “In patients with MS, vaginal delivery is favoured if obstetric factors are favourable, with the use of assisted delivery devices during the second stage to avoid the need for pushing and to shorten the second stage.

• Severe MS with severe pulmonary hypertension is associated with increased maternal and fetal risk during labour. This situation requires multidisciplinary team care and carefully-planned delivery, usually by elective Caesarean section with invasive haemodynamic monitoring.”

The role of the anaesthesiologist begins by providing good labour analgesia.

- Most reports have recommended vaginal delivery under epidural anaesthesia, unless obstetrically contraindicated.

- Caesarean section is indicated for obstetric reasons only.

- Combined spinal–epidural analgesia during labour using intrathecal fentanyl 25mcg produces good analgesia without major haemodynamic changes during the first stage of labour.

- During the second stage of labour, only the uterine contractile force should be allowed rather than the maternal expulsive effort that is always associated with the valsalva maneuver. Therefore, the second stage of delivery should be cut short by instrumentation.

- Supplementary analgesia for instrumentation with slow epidural boluses of fentanyl and a low concentration of bupivacaine reduces SVR and the cardiac pre-load. Low spinal anaesthesia for vaginal instrumental delivery has also been used with good results in these patients

- Labour pain can affect multiple systems that determine the uteroplacental perfusion. Hence, foetal heart rate monitoring should be carried out during all stages of labour.

- Supplemental oxygen administration with pulse oximetry monitoring to minimize increases in pulmonary vascular resistance and maintenance of left uterine displacement for good venous return are mandatory.

- Supplementary epidural anaesthesia can be maintained throughout the immediate post-partum period and the catheter left in situ could provide anaesthesia for immediate or post-partum tubal sterilization.

12. What is the medical management MS?

Medical therapy for stenotic lesions in symptomatic women consists of

✓ HR control with β-blockers and

✓ Restriction of physical activity and

✓ Preload reduction with diuretic agents (class I recommendation).

➢ Metoprolol is the preferred β-blocker because atenolol has been linked to adverse fetal outcomes, including intrauterine growth retardation and preterm delivery. HR control leads to improved LV filling and lower LAP.

➢ Diuretic use, in particular, must be accompanied by monitoring for signs of uteroplacental insufficiency.

➢ Atrial fibrillation requires aggressive treatment with digoxin and beta blockers to revert it to sinus rhythm and

➢ Anticoagulation to prevent systemic embolization.

➢ Cardioversion should be performed if pharmacologic therapy fails to control the ventricular response. Anticoagulation, even in the absence of atrial fibrillation, is beneficial.

➢ Due to the high incidence of embryopathy during the first trimester and bleeding during parturition, warfarin should be used during 12–36 weeks of pregnancy only.

Antibiotic prophylaxis for endocarditis is reserved only for patients with a previous history of endo carditis or presence of established infection.

➢ About 50% of patients with severe MS will develop heart failure symptoms during pregnancy. Shortness of breath NYHA Class ≥II is an independent predictor of maternal cardiac events during pregnancy.

➢ Volume overload symptoms are treated by diuretics such as furosemide, which should be prescribed cautiously for a short period of time (Class IIb recommendation), together with restriction of dietary salt intake.

➢ Excess diuresis can reduce the amniotic fluid volume and causes foetal distress.

13. How will you manage anti-coagulant in pregnancy?

✓ SC/IV heparin for up to 12 weeks antepartum (aPTT 1.5–2.5-times of normal)

✓ Warfarin from 12 to 36 weeks (maintain INR 2.5–3.0)

✓ SC/IV heparin after 36 weeks. Therapy with low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) instead of unfractionated heparin is gaining popularity.

✓ Although an “anti Xa” activity is used to monitor LMWH, no anti-Xa activity-based guidelines have been issued till date.

14. What are surgical management of MS during pregnancy?

➢ Patients with MS or AS whose conditions are refractory to medical therapy may be candidates for percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty, which should be performed with abdominal shielding and delayed until after the first trimester if possible to minimize the radiation risks to the fetus (class IIa recommendation)

➢ If mitral stenosis is diagnosed before pregnancy, mitral commissurotomy is preferred.

➢ During pregnancy, the second trimester is the preferred period for any invasive procedure. Percutaneous valvuloplasty using the Inoue balloon technique has become the accepted treatment for patients with severe symptomatic mitral stenosis.

➢ Percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty provides palliation for pregnant women with mitral stenosis, and the reported success rate is nearly 100%. Successful balloon valvuloplasty increases the valve area to >1.5 cm2 without a substantial increase in mitral regurgitation.

➢ Although the maternal outcome in percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty and open commissurotomy are the same, the foetal loss is high in open commissurotomy, at a ratio of 1:8.

➢ Valve replacement is reserved for severe cases with calcified valve and in mural thrombus where the maternal mortality is 1.5–5% and the foetal loss is 16–33%.

➢ Surgical options, either open or percutaneous, are the treatment of choice in severe symptomatic MS.

➢ In patients with valves with mobile leaflets that are free of calcium, percutaneous mitral commissurotomy (PMC) is the preferred option. This is performed by passing a balloon across the valve and inflating it, thereby splitting the fused commissural edges.

➢ PMC achieves an MV area >1.5 cm2 with no worse than moderate mitral regurgitation (MR) in 80% of cases, with emergency surgery rates of <1%.

➢ Surgery is recommended in the presence of atrial thrombus, heavy valve calcification, or when another open cardiac procedure needs to be performed.

➢ Mitral valve replacement is now the preferred treatment due to improved valve and clinical outcomes. Mitral valve replacement has an operative mortality of 3–5%, but long-term outcomes are highly variable and related to multiple patient-related factors (e.g. bi-ventricular function, pulmonary pressures, and AF) BJA 2017.

Different types of artificial heart valves:

- Starr-Edwards Valve. Starr-Edwards Valve. Smeloff-Cutter Valve.

- Caged ball valve.

- Tilting-disc valve.

- Bileaflet valve.

- A replaceable model of Cardiac Biological Valve Prosthesis.

- Hufnagel heart Valve

15.What are the goals for the anaesthetic management of patients with mitral stenosis?

1. Maintenance of an acceptable slow heart rate,

2. Immediate treatment of acute atrial fibrillation and reversion to sinus rhythm,

3. Avoidance of aortocaval compression,

4. Maintenance of adequate venous return,

5. Maintenance of adequate SVR and

6. Prevention of pain, hypoxaemia, hypercarbia and acidosis, which may increase pulmonary vascular resistance.

➢ One of the major advantages of epidural analgesia is that it can be administered in incremental doses and that the total dose could be titrated to the desired sensory level.

➢ This, coupled with the slower onset of anaesthesia, allows the maternal cardiovascular system to compensate for the occurrence of sympathetic blockade, resulting in a lower risk of hypotension and decreased uteroplacental perfusion.

➢ Moreover, the segmental blockade spares the lower extremity “muscle pump,” aiding in venous return, and also decreases the incidence of thromboembolic events.

➢ Invasive haemodynamic monitoring, judicious intravenous administration of crystalloid and administration of small bolus doses of phenylephrine maintain maternal haemodynamic stability.

➢ Anesthetic options for Cesarean section include incrementally dosed lumbar epidural or general anesthesia.

➢ In general, an incrementally dosed lumbar epidural will provide the least amount of hemodynamic alteration.

➢ General anesthesia may provide very stable hemodynamics if the sympathetic stimulation associated with laryngoscopy and intubation are attenuated either by use of anesthetic agents or β blockade.

➢ During the intraoperative period as well, adequate depth of anesthesia is required to avoid tachycardia and hypertension.

➢ General anesthesia provides the advantages of definitive airway control and the ability to use transesophageal echocardiographic monitoring throughout the procedure.

➢ A number of case reports have described the use of general anesthesia with good maternal and fetal outcomes.

➢ Opioid-based techniques are often recommended for anesthesia in patients with severe valvular disease because they have a minimally depressive action on the cardiovascular system and provide excellent analgesia.

➢ In the case of Cesarean section, however, this technique could result in prolonged neonatal respiratory depression.

➢ Remifentanil is a synthetic opioid that provides intense analgesia of rapid onset and short duration.

➢ Remifentanil crosses the placenta but appears to be rapidly metabolized and redistributed in mother and fetus.

➢ Thus, remifentanil has the ability to provide intraoperative hemodynamic stability and rapid maternal emergence and recovery from general anesthesia while preventing prolonged neonatal sedation and respiratory depression.

➢ Because of the need to avoid uterine atony, large doses of inhalation anesthetics have to be avoided.

➢ If general anaesthesia is contemplated, tachycardia, inducing drugs like atropine, ketamine, pancuronium and meperidine, should be totally avoided.

➢ A beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist and an adequate dose of opioid like fentanyl should be administered before or during the induction of general anaesthesia.

➢ Because esmolol has a rapid onset and short duration of action, it is a better choice in controlling tachycardia. Since foetal bradycardia has been reported after esmolol, foetal heart rate should be monitored.

➢ Modified rapid sequence induction using etomidate, remifentanyl and succinylcholine is an ideal choice in tight stenosis with pulmonary hypertension.

➢ Maintenance of anaesthesia can be carried out with oxygen and nitrous oxide 50:50, isoflurane, opioids and vecuronium.

➢ With associated severe pulmonary hypertension, nitrous oxide can be omitted. At this juncture, invasive haemodynamic monitoring is an inevitable guide.

➢ After delivery of the fetus, oxytocin 10–20 U in 1,000 ml of crystalloid should be administered slowly. It can lower the SVR as well as elevate the PVR, resulting in a drop in cardiac output.

➢ Methylergonovine, or 15-methylprostaglandin F, produces severe hypertension, tachycardia and increased PVR, so is avoided.

16. What are the monitors preferred in MS?

Use of invasive monitoring depends on the complexity of the operative procedure and the magnitude of physiologic impairment caused by the mitral stenosis. Monitoring of asymptomatic patients without evidence of pulmonary congestion need be no different from monitoring of patients without valvular heart disease. On the other hand, TEE can be useful in patients with symptomatic mitral stenosis undergoing major surgery, especially if significant blood loss is expected. Continuous monitoring of intraarterial pressure, pulmonary artery pressure, and left atrial pressure (pulmonary artery occlusion pressure) should be considered.

17. How will you manage MS patients intra operatively?

Problems:

Sinus tachycardia or a rapid ventricular response during atrial fibrillation.

Marked increase in central blood volume, as associated with overtransfusion or head-down positioning.

Drug-induced decrease in systemic vascular resistance.

Hypoxemia and hypercarbia that may exacerbate pulmonary hypertension and evoke right ventricular failure.

If possible, Sinus rhythm should be maintained, and a low normal heart rate (<70 beats min−1) is critical regardless of the rhythm to allow sufficient diastolic time for ventricular filling. Aim for normovolaemia, the fluid boluses can worsen pulmonary oedema. Because the cardiac output is fixed, any reduction in systemic vascular resistance can cause a decrease in coronary perfusion pressures. Afterload maintenance is therefore crucial. Pulmonary vascular pressures should be optimized by avoiding hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis to prevent acute right ventricular decompensation. Nitrous oxide should not be used as it can cause further increases in pulmonary vascular resistance in those patients where it is already elevated.

The LV will usually be unaffected. The right ventricle may need support if signs of failure are present. After ensuring pulmonary vascular resistance is as low as possible, inotropes such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors or catecholamine agonists may be required to augment the right ventricular contractility. Care should be taken with phosphodiesterase inhibitors due to their vasodilating effects on the systemic system resulting in afterload reduction and hypotension.

18. Are all valve lesions problematic, or are there specific situations that you have to focus on in the pregnant woman?

➢ Many valve lesions in pregnant women are well tolerated. For example, a pregnant woman should be able to tolerate mild or moderate degrees of mitral or aortic regurgitation, particularly with normal left ventricular function and no evidence of heart failure.

➢ Even severe asymptomatic mitral or aortic regurgitation can be managed conservatively with careful follow-up.

➢ On the other hand, there are several lesions that are dangerous enough to the welfare of the mother and fetus that pregnancy should be strongly discouraged and/or prematurely terminated depending on its stage.

➢ These valve lesions include severe aortic stenosis, as well as severe symptomatic mitral stenosis, especially when pulmonary hypertension is present.

➢ In contrast to regurgitant lesions, severely stenotic lesions are very poorly tolerated and best treated prior to conception.

➢ Primary pulmonary hypertension and Eisenmenger’s syndrome are two other disease states for which pregnancy is contra-indicated. For poorly understood reasons, it is commonly during the first week post-partum that the Eisenmenger’s woman is at greatest risk.

➢ There are other heart valve lesions that should be considered relative contraindications to pregnancy, such as a mechanical heart valve requiring anti-coagulation. There is simply no single best approach to this extremely challenging situation. Practice patterns vary between the US and Europe, but maternal and fetal outcomes are significantly compromised regardless of the choice of anti-thrombin agent or agents.

➢ Finally, we should mention pregnancy and Marfan syndrome, which is commonly associated with dilatation of the aortic root and varying degrees of aortic regurgitation. A root or ascending aortic dimension in excess of 4.0 centimeters is considered a relative contraindication to pregnancy, because of the increased risk for spontaneous rupture or dissection.

19. Let’s say a patient comes to your office and she has a valve prosthesis and she is on warfarin. She announces that she is pregnant. How do you approach it at that point?

➢ This is a very tricky and controversial situation. Assuming that the mother and her partner wish to proceed with the pregnancy, they should first be educated about the hazards of warfarin or heparin anticoagulation, alone or in sequence, throughout pregnancy and in the peri-partum period. Whatever strategy is chosen, the mother should be counseled that the use of anticoagulant therapy during pregnancy — despite the best of intentions and the most careful of protocols — is still associated with a significant risk of adverse outcome for both mother and fetus.

➢ The risks include

✓ Prosthetic valve thrombosis,

✓ Maternal thromboembolism,

✓ Hemorrhage,

✓ Premature labor,

✓ Spontaneous abortion,

✓ Fetal wasting,

✓ Embryopathy,

✓ Neurodevelopmental abnormalities, and

✓ Abruptio placenta.

✓ Whereas warfarin crosses the placenta, heparin does not.

➢ There are a couple of approaches that the valve guidelines committee struggled with around this issue. We paid careful attention to the recommendations of the American College of Chest Physicians and recognized that practice patterns differ between the US and Europe.

➢ One approach is to consider using low molecular weight heparin, on a dose-adjusted basis, throughout the pregnancy. By dose-adjusted, I mean as predicated on anti-Xa levels which are expected to change during the course of pregnancy. A similar approach can be tried with dose-adjusted subcutaneous unfractionated heparin as titrated against aPTT levels. We believe that it’s important to maintain either anti-Xa or aPTT levels within strictly defined ranges throughout pregnancy, though large scale clinical trials are lacking.

➢ A second option would be to use heparin (either unfractionated or low molecular weight) during the first trimester because the risk of warfarin-related embryopathy seems to be highest with exposure between week 6 and week 12. Many authorities recommend that if the mother is on warfarin at the time of her initial encounter with the cardiologist, she should be transitioned to heparin and then consider resumption of warfarin beginning in the second trimester with continuation until approximately week 36. At that time, it would be appropriate to substitute heparin for warfarin leading up to labor and delivery, with resumption of warfarin after delivery.

➢ Warfarin is not transmitted to the nursing baby. It should be noted that many US cardiologists, obstetricians, and mothers have opted against the use of warfarin at any time during pregnancy, in contrast to practice patterns in Europe where practitioners have advised consistently that warfarin is safe, provided that the daily dose is kept below 5 mg, and more effective than heparin in high-risk situations. A third and rarely used strategy would be to consider the use of intravenous unfractionated heparin throughout pregnancy via continuous infusion. This approach has proved difficult, even for shorter periods of exposure (as for example between week 36 and delivery).

➢ One scenario we see is the patient with mitral stenosis who becomes pregnant and we’re asked to look at that patient and recommend some therapy in anticipation of problems that might develop.

➢ One always wishes to avoid interventional procedures in a pregnant patient. Many pregnant women with severe mitral stenosis can be managed with aggressive rate control measures and the judicious use of diuretics. There are rare times, though, when decompensation during pregnancy requires an intervention.

➢ There are several case series about the successful use of balloon valvuloplasty in women with mitral stenosis. The procedure is done with transesophageal echocardiography so as to reduce fluoroscopy time and is a reasonable strategy for women with severe mitral stenosis who have developed complications of heart failure.

20. MITRAL STENOSIS – Ten Rules for Anesthesia Considerations:

1. Goal:

Preload is normal or increased. Afterload is normal Goal is controlled ventricular response. Avoid tachycardia, pulmonary vasoconstriction.

2. The most important hemodynamic goal is to avoid tachycardia (keep heart rate within its normal range). Tachycardia is poorly tolerated because of the decreased time for diastolic filling. In case of atrial fibrillation digoxin should be continued perioperatively. Short-acting β-blockers can then be used for heart rate control. Premedication with narcotics or benzodiazepines preferred. Avoid excessive sedation which may result in hypoxemia or hypercarbia leading to increase in PHT.

3. Left ventricular preload should be maintained without exacerbation of pulmonary vascular congestion. Appropriate replacement of blood loss and prevention of excessive anesthetic-induced venodilation help preserve hemodynamic stability intraoperatively.

4. Avoid factors that aggravate pulmonary hypertension and impair right ventricular function. Every effort should be made to avoid increases in pulmonary arterial pressures (e.g., avoid hypoxia, hypercardia, acidosis, lung hyperexpansion, and nitrous oxide). Newer therapeutic options for treatment of refractory pulmonary hypertension include inhaled prostacyclin or nitric oxide.

5. Medications taken by the patient before surgery to control heart rate, such as digitalis, β-blockers, calcium receptor antagonists, or amiodarone, should be continued in the perioperative period.

6. Control of the ventricular rate remains the primary goal in managing patients with AF, β-blockers and calcium-receptor antagonists may be required intraoperatively although cardioversion should not be withheld from patients with atrial tachyarrhythmias who become hemodynamically unstable.

7. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring CVP, PAC and arterial catheter facilitates timely recognition of hemodynamic derangements.

8. Left ventricular contractility and SVR are usually preserved in MS. Right ventricular dysfunction probably poses a greater challenge in treating patients with MS. Inotropic support may be needed for patients with secondary right ventricular dysfunction or failure. Epinephrine and milrinone are good therapeutic options.

9. Use generous amount of opioids to abolish hemodynamic response to intubation. Remifentanil, alfentanil or fentanyl can be used. Patients with moderate to severe MS generally have slow circulation that prolongs arm-brain circulation time. Induction agents should be double diluted and given slowly in titrated doses (sleep dose) till patient goes under. Etomidate is the best agent for hemodynamic stability but midazolam or thiopentone can also be used. Propofol should be avoided. Vecuronium, atracurium or rocuronium can be used. Pancuronium should be avoided. Volatile anesthetics such as isoflurane, desflurane, or sevoflurane can be administered. Halothane is best avoided; In patients with pulmonary artery hypertension nitrous oxide is best avoided due to its effects on pulmonary resistance.

10. Neuraxial anaesthesia causes a decrease in afterload, and so has the potential for profound hypotension in MS. This may lead to a spiral of poor myocardial perfusion and worsening cardiac function. As such, the decision to undertake neuraxial anaesthesia in MS should not be made lightly. Consideration should also be given to the fact that the patient may be anticoagulated.

Ref:

1. Kannan M, Vijayanand G. Mitral stenosis and pregnancy: Current concepts in anaesthetic practice. Indian J Anaesth 2010;54:439-44.

2. Menachem M. Weiner, Torsten P. Vahl, Ronald A. Kahn; Case Scenario: Cesarean Section Complicated by Rheumatic Mitral Stenosis. Anesthesiology 2011;114(4):949-957.

3. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease.

4. The American College of Cardiology’s Cardiosource. Management of Valvular Heart Disease in Pregnancy. Patrick T. O’Gara, M.D., F.A.C.C.; Albert E. Raizner, M.D., F.A.C.C.

5. Delivery in women with mitral stenosis (query bank). RCOG 6. Mitral stenosis in pregnant patients. Dr. Ghada Sayed Youssef. E-Journal of Cardiology Practice.

Ref: Further Reading

1. KAPLAN’S CARDIAC ANESTHESIA: FOR CARDIAC AND NONCARDIAC SURGERY: SEVENTH EDITION

2. CHESTNUT’S OBSTETRIC ANESTHESIA: PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE, FIFTH EDITION